What Is Study?

Study is a form of learning that can function as a virtue—a way of life that leads to fuller and richer human flourishing. Like all virtues, study depends on a set of systematic practices and moods. We call these habits of study. Finally, study is the verb that describes the process of exercising these habits.

A Virtue

Study is, first and foremost, a virtue. It is a human good – a way of life that leads to fuller and richer forms of flourishing. It is similar to other ethical qualities like love, courage, hope, and justice, and very different from skill sets such as reading, arithmetic, or basketball. “Study skills” is almost a contradiction. Study is not a set of skills. It is a passion.

The passion to study – the desire to appreciate the world around us, to explore it, to communicate about it, and to understand it – is part of our human nature. It should not require external rewards and punishments to motivate human beings to study, just as we should not need to be incentivized in order to love our friends, cheer for our children’s sports teams, or enjoy a healthy meal. The passion of study has many names: “lifelong learning”, “curiosity”, “open-mindedness”, “thirst for knowledge”, or “desire to understand.” Human beings who adopt study as one of their cardinal virtues are called “students.” They do not always attend schools, and they are not necessarily children.

Elementary, middle and high schools exist to communicate and promote study and to teach the habits that support it.

A Set of Habits

As a virtue, study is both a disposition and a set of habits – systematic practices that support this desire and make possible its fulfillment. The supporting habits for study are careful attention, sincere appreciation, profound reflection, dialogue and inquiry, and various interpretive skills. These are, for us, the core curricular concerns. They are more central and important than any particular academic discipline or skill. We are obsessively concerned with finding the most compelling curriculum and the best teaching practices, but this is because they will tend to reinforce and foster the habits described above.

A Process

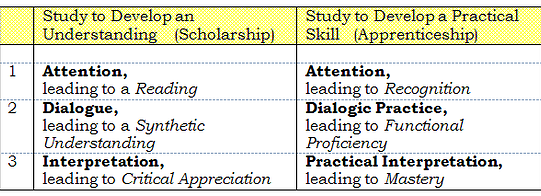

Study is a form of learning. We distinguish study from types of learning that occur unconsciously, spontaneously, by accident, or as a by-product of some other exercise. Study is learning motivated by the desire to learn. We study something when we set out consciously to learn it. There are two kinds of things we can set out to learn, and therefore there are two main forms of study. Again, we distinguish these branches by looking at their ultimate goals. Scholarship is a form of study that aims at a deeper or more profound understanding. We practice scholarship when we set out to study a text or a work of art, for example. Apprenticeship is a form of study that aims at developing a skill which can be performed. We practice apprenticeship when we set out to study a sport or a musical instrument, for example. There are no hard and fast boundaries between these two forms of study. The scholar who studies English poetry in order to gain a critical appreciation will often operate as an apprentice, learning to write the forms of poems she is studying. The apprentice who studies the skills necessary to play the guitar may also operate as a scholar in the areas of music theory and the history of his instrument. There are similar examples in Art education. Scholarship and apprenticeship go hand in hand.

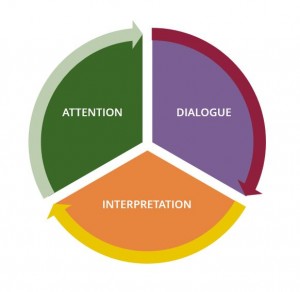

We believe that study always occurs in three steps: attention, dialogue, and interpretation. First the student attends to the object of study. After attending closely, she engages in a dialogue, and that dialogue results in an interpretation.

This process can be accomplished in the blink of an eye, or it can consume vast amounts of time. Imagine an experienced rock climber who sets out to climb a wall for the first time. She wishes to gain a greater understanding of the wall in order to climb it more effectively, so she studies it. Briefly, she looks the wall over. This is her attention phase. If she is with another climber, she will probably start to talk over what she sees, suggesting and discarding ideas for good handholds and possible routes. If she is alone her dialogue will take place in her own head. In solitary study dialogue is replaced by reflection, but we believe reflection is itself dialogical. The climber will still suggest, ratify, discard, and decide. Finally, she will have arrived at an interpretation: her personal understanding of the surface. Another climber might interpret it differently, but would use the same process.

To take a different example, imagine a high school student learning the craft of creative writing. At first, he learns to appreciate the works of masters (attention). Later, he imitates them, and his imitations are critiqued by his teachers and by others involved in learning the same techniques. In effect, he engages in dialogic practice. Finally, he not only understands the skill in theory, but has a personal style of writing– an interpretation– that distinguishes his form of practice from that of his fellow students. He is working toward mastery of the skill.

As we can see, this three-part system of attention, dialogue and interpretation differs slightly depending on whether the student is involved in scholarship or apprenticeship. The difference looks like this:

What is the best way to study?

Different students have different ways of approaching study, and no single method will work best for everyone. However, some things will almost always lead to better results. The “best” way to study is to study armed with a real appreciation of what study is and how it proceeds. If study is, as we believe, a process of attention, dialogue, and interpretation, the best schools will teach their students to appreciate that process and how it works best, individually, for each of them.

In this way, study is a lot like diet. There are thousands of different diets that will lead to good bodily health. Many people will achieve good health in a variety of ways. There is no one best diet for everyone; and good diets vary according to the specific metabolisms of the people consuming them. However, if our goal is good health, it is clear that the more we know about health, food, and the way food is processed by the body, the better our chances of achieving the goal. The same goes for study. The best study is informed study, and the strongest scholars and apprentices know what the process of study is and how it works.